.jpeg) |

| Archaeologist Danielle Kurin is gone but not entirely forgotten in the UCSB anthropology building |

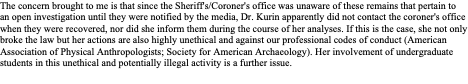

Last January, most members of the University of California, Santa Barbara anthropology department breathed a deep sigh of relief when one of their colleagues, archaeologist Danielle Kurin, abruptly resigned the tenured position she had fought years to get. Kurin's departure seemed an appropriate, if long delayed, resolution of her years of well-established abuses and enabling of abuse, leading to a Title IX, censure by the university, three years of administrative leave, ejection from a leading archaeological organization, and other dramas. (For a guide to my reporting on all these matters, please see here.)

In the midst of all these events, Kurin filed an $18 million defamation suit against me in federal court. Before the case was settled (and later unsettled after she violated our agreement), my attorneys and I received thousands of pages in discovery, which not only fully backed up my reporting but provided even new details of her misconduct. Unfortunately, to avoid months of litigation, we had to agree to a court "protective order" to get most of these documents in a timely manner; the court order prevents me from revealing what was in them.

However, many of the documents, at least those that involve UCSB directly, are accessible via the California Public Records Act. I began requesting selective records soon after the case was over. The university has taken months to process them, but is finally releasing them to me in batches. This post is an update on two issues important to understanding why Kurin is no longer at UCSB: Her 2018 settlement with the university after the Title IX proceedings, which included the three year administrative leave; and indications that the university had investigated Kurin for possible misconduct during her anthropological work for the mother of a missing teenager, victim of the 2018 Montecito mudslide (Montecito is a community just next to Santa Barbara.)

As I write, the Santa Barbara County Sheriff's office has not yet wrapped up its investigation of Kurin's claim that she had found the remains of Jack Cantin, whose mother has never given up the search for her missing son. According to Raquel Zick, spokesperson for the Sheriff, this is now due mostly to continuing negotiations in a lawsuit that Jack's mother, Kim Cantin, filed against the county and the sheriff because it would not give her a death certificate for the bones that Kurin and her student team had supposedly found.

This means that the Sheriff and coroner have probably concluded their attempts to identify the human remains, although we are awaiting official word about that. The new documents shed some light on the role of both Kurin and the university in this and other matters, and I will go through them in what follows.

Kurin's 2018 settlement with UCSB: Three strikes and you're out.

In 2016, after Danielle Kurin was found in a Title IX proceeding to have retaliated against students who reported her partner (and later husband) for acts of sexual harassment at her archaeological field sites in Peru, she sued the University of California on the grounds that they had denied her a promotion despite the disciplinary action. The case dragged on for nearly two years. But in March 2018, the university settled all claims with Kurin. The settlement was never made public, nor even the details of the Title IX, even to members of Kurin's department. In February 2020, based also on a public records release, I first reported on the Title IX; now, for the first time, I can publish the settlement, which is accessible here.

What follows is brief commentary on some of its provisions. Note that only one section is partly redacted, which I will explain.

Sections 1-4: These are fairly standard provisions in a settlement of this kind, and spell out when Kurin can return to full compensation as an assistant professor

Section 5: Kurin is banned from the UCSB campus for the three years of her leave, except for supervised removal of materials from her office and lab. Given her confirmed retaliation against students, this provision was presumably to protect them from possible abuse at her hands.

Section 6: Kurin's "tenure clock" is suspended until she returns to work at UCSB. Note that while the university could have fired Kurin--and in such similar, egregious circumstances, many institutions have done just that--the UCSB administration (and probably the University of California central administration) decided to give her another chance, for reasons they have never explained to anyone.

Section 7: This section refers to the Letter of Censure put into Kurin's personnel file for the three years she was on leave. I earlier published this letter, as part of the settlement agreement in the Kurin v. Balter lawsuit, but I am linking here to the better quality version I received via the California Public Records Act. The Letter of Censure, which Kurin and her attorney attempted to hide from me and my attorneys during the lawsuit, details the charges the university confirmed against her. It demonstrates clearly that she lied to the court and to her colleagues about the nature of the discipline against her and the reasons for it.

Section 8: This section forbids Kurin from knowingly working with any UCSB students during her leave. I have no evidence that she did so. However, as I reported earlier, the Institute for Field Research allowed Kurin to bring students from other institutions down to field schools in Peru in 2017 and 2018 despite its knowledge that she had been subject to a Title IX; that led to a sexual assault against a student in 2018 at the hands of Kurin's then husband.

Section 9: This is the only section which includes redactions, and only partially. The unredacted part indicates that before Kurin can return to work, a psychotherapist must certify that she is fit to return to do so. I have reported earlier, based on independent sources, that the settlement required Kurin to undergo an extended period of psychotherapy. The redactions were presumably for privacy reasons. However, those who know Kurin say that she has had mental health issues for years, and that her family has been greatly concerned with that. This could generate some sympathy for Kurin, but condemnation of those who allowed her to continue to abuse students in various ways and enabled her legal attacks on those who told the truth about her.

Sections 11-31: These sections are again pretty standard legalese typical of such settlements and not particular to Kurin's situation.

Section 32: In terms of what happened later, this is probably the most important provision of the agreement. It outlines what could happen to Kurin if she commits similar misconduct again. In brief, she would be subject to dismissal with no right of appeal.

![The truth at last, or at least some of it, about Peter Rathjen, the U of Adelaide, the U of Melbourne, the U of Tasmania, etc. [Updated Sept 3, 2020: University of Melbourne "leader" finally speaks]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhTTYlLfJJPciFfe5iknlB2hbK8jYC5SDgoJTGaFKZBvgKVDAjUHzXjHFifYPzrixQgmQPW0Udsk6Y3OMLjmJd4rCxY352IA9Nwt2DlSscScArhuGqGpsiLozqx1A2xzK2I0_u_HOjwQlfn/w680/Rathjen.jpg)

0 Comments